Aretae has a problem with authority.

I’ve never been able to understand authority as anything other than thugs with bigger sticks

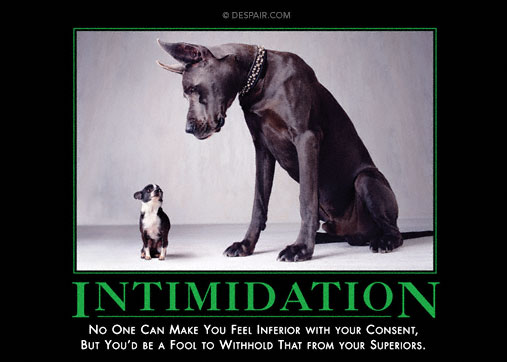

Well, sure. That goes without saying. But thugs with bigger sticks are a fact of life, unless you set out yourself to be the biggest thug of all. Which, despite his having “chosen reason over authority”, does not seem to have been Aretae’s plan (I’m not sure exactly how to go about it, but I doubt it would leave much time for cookery).

This is a step back from our previous discussion, because it’s not about formalism versus democracy, or monarchy versus neocameralism, it’s about law versus anarchy.

The metaphor I would prefer, though, is not a “step back”, but a step down. Morality, or “Right Conduct”, like system architectures, has layers*.

The base layer is absolute imperatives. These pretty much have to be supernatural, or else non-existent. Aretae believes that nobody can give him an order that he absolutely must obey. I agree. At that layer, I am an anarchist:

There is no God but Man

Man has the right to live by his own law

blah blah blah…

Man has the right to kill those who would thwart those rights.

Having deified my own reason and my own appetites above all alleged authority, I can now follow them to get what I want.

The technology risk/governance types in a large organisation come up with rules about what a programmer on the coalface is allowed to do to the company’s precious systems. They frequently come up with rules for application code, and rules for configuration. If they’re not careful, or not expert, they end up with definitions that either classify java bytecode as configuration for the jvm, or else classify users’ spreadsheets as application code. Code and configuration really aren’t different things, they’re just different layers. They smell the same.

If Aretae starts to construct rules of thumb for how to act by his own reason for his own appetites, those rules will smell a lot like morality. They may not actually be ultimate imperatives that he has to obey, but then java bytecode isn’t actually machine instructions that are executed by a CPU.

So when I argue for authority, I do so not on the basis of ultimate morality, but on the basis of what works better for me. I don’t shy away from the words, however, because of the remarkable resemblance between what I reason to be the most utilitarian form of government, and what was once believed to have been imposed by supernatural forces. It is too close to be coincidental — I think for most people, they would be better off accepting the old morality and getting on with their cooking.

Further, the “no authority” attitude is not antithetical to formalism. The real opponents of formalism are those who do believe that some forms of government have an ultimate moral legitimacy that others lack. Aretae and I believe that all governments are ultimately “thugs with bigger sticks”, and the argument is not about which has more moral authority, but about which works better for us. That argument of course remains unresolved, but that’s because TSID, not because of different fundamental assumptions.

* Also like onions. And ogres. Both of which smell.