28 March 2020

We’re about a month in to a one-in-a-lifetime happening. I want some kind of record of what I was thinking and doing. Most of my thinking is out loud on Twitter, so I’ll be dredging that for material.

“Plague Year” is probably a misnomer. I don’t expect this to be over in 2020.

It started for me in January. An epidemic in Wuhan wasn’t terribly interesting, but @MorlockP on Twitter posted that he saw it as likely to become a global pandemic, and was making preparations for a prolonged isolation. I followed his reasoning, and told the family after dinner that it looked like getting bad, and we should make sure we had long-term stocks in the house for food, water and cleaning equipment. Over the following couple of weeks we bought large plastic boxes and filled them with emergency supplies.

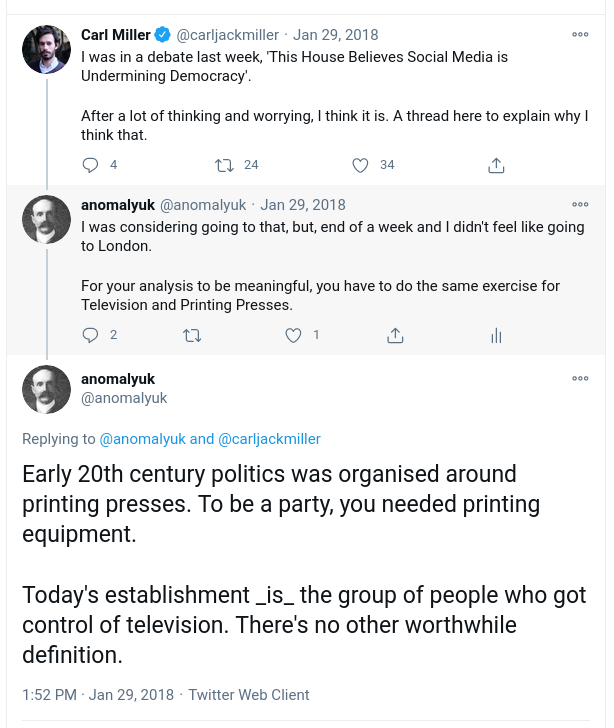

Several other people have said they were spurred into preparations by MorlockP’s tweets. Twitter locked him out of his account a week ago, ever careful to protect us from misinformation.

I remember when I was planning to go to London on January 31st, to celebrate Brexit, I contemplated whether it was safe to head into crowds and underground trains. I decided that it was still early and we could go without worrying, but it might be the last time. I haven’t been in London since.

Things moved slower than I expected through February. We built up our stocks, I mentioned it to friends and colleagues, who thought I was a bit silly. Curtis Yarvin’s American Mind piece asserting that globalism would be ended by pandemics like this one was 1st Feb.

On February 22nd I retweeted a UK government notification, that 9 positive cases of COVID19 had been found in Britain.

By the end of February it was still only a minor subject on Twitter: @thespandrell had already started calling it “boomerpox”, one or two others were saying they had stocked up, Nick Szabo was complaining that the FDA was preventing testing from happening in the US.

By March 2nd, I’d stopped going swimming. It seemed an unnecessarily easy way to catch a virus. I kept going to the gym for a few days more. I’m now back to my pre-gym self: not exercising and living on bread and biscuits. I’m going to put on 20lbs and lose a lot of strength before this is over .

The virus was still behind the US presidential primaries and Georgina Bloomberg’s horse novels in volume of discussion on my twitter timeline

I heard a friend of a friend story that the NHS was putting testing pods in every hospital, and were generally gearing up for a major crisis.

By March 9th, the argument had started about whether the British Government was doing enough, or whether it should be closing schools and stuff. “Flattening the curve” had appeared as a concept, illustrated with what I consistently refer to as the graph-with-no-scale.

Gregory Cochran posted his “nuke the curve” piece on the 10th, arguing that it was necessary to eliminate the virus, not just slow the spread. I expressed scepticism over the feasibility, given that if infection rates were kept very low, it would keep reappearing for a long time.

On March 11th, I saw a tweet by @vaughanbell. “If you want to make sense of why the UK government are making the decisions they are making with regard to coronavirus: they have prepared over the last decade for a pandemic (focusing on pandemic flu) and the strategy and evidence based is public”, with a link to the Pandemic Flu planning information document. I studied this. I noted that the plan anticipated a lot of deaths — it advised local authorities to be prepared for “210,000 to 315,000 additional deaths across the UK over a 15-week period”. I noted that the focus of the plan was on keeping government going, not on minimising deaths, and not at all on preventing infections. I tweeted, Most of the strategy document is explicitly ‘we’re all going to get it, so just carry on’. I noted that COVID19 was spreading faster and causing more hospitalisations than the government plan had anticipated, writing What I hope is that behind the summary strategy document, there’s a range of contingency plans that includes this fast-spreading high-hospitalisation extreme. But they’re not showing it. At time of writing, 28th March, these points are still the centre of the arguments.

The 12th of March was the last day I went to work. I find I work more effectively in an office with my colleagues, but I always was able to work from home on occasion, and I’ve been doing it now for two weeks.

The evening of 12th of March, before I left the office for (so far) the last time, I watched Boris Johnson’s press conference. This was where it really became clear that the government was expecting at the very least tens of thousands, and possibly hundreds of thousands of deaths, didn’t believe it could prevent the virus spreading through the entire population, and wasn’t going to try. I wrote a blog post on my understanding.

Though shocked, I believed, and still believe, that that was a sensible position. As I had suggested to Cochran, though some countries in Asia had reduced the size of the epidemic, nobody had proved that it could be eliminated, or that the measures taken to reduce it could be sustained for the duration that would be required.

I was in a minority, at least within my twitter community. I spent the next four days largely arguing with people who believed the UK strategy was insane or was being changed.

The strongest objection is Taleb’s. His central point is the one that made his name, that mathematical modelling of unknown situations will systematically underestimate the probability of extreme outcomes. He is right. His deduction from that is that governments should take extreme measures to combat the pandemic, because nobody knows how bad it could get. My objection to that is that the outcome of the extreme measured being taken is also an unknown situation, where we do not know how bad it could get. I don’t think it will lead to the collapse of states and a new dark age, but I don’t think the virus will kill two million people in Britain either. How to model the probability of either of these outcomes? Taleb’s whole argument is that you can’t.

Still, it is the best argument for trying to put the brakes on and at least buy some time to get better information. And it seems that my claims through the weekend of 14-15 March that the UK government was not changing course were wrong. Though they are being obfuscatory about it, the models from Imperial College they are using are now modelling “suppression” rather than “slowing”. Unlike under the previous, clear, strategy, there is now no long-term outcome described.

Here of course we are into the realm of politics. “We do not really know what is going to happen, so we’re trying to keep the disease under control for now and we’ll make more decisions later” may be the most rational position, but it doesn’t sound good on TV.

The other news was that a revision of the Imperial College model had shown much more demand on hospitals than had been foreseen earlier, and that therefore different measures would have to be taken to ensure patients could continue to get care. I was and am mystified by this. Firstly, that was obvious from the start — I had tweeted on the 11th that the hospitalisation rate was going to be the really nasty bit, and my interpretation of the announcement on the 12th was that the government knew that hospitals were going to get much worse than even the horror stories we had already heard from Italy. At the same time, if they believed on the 12th that it was not possible to prevent the virus spreading through the population, how did that become possible on the 13th just because the hospitalisation rate was worse? My guess is that in reality there was an ongoing division in the cabinet and the cabinet office over whether to slow or suppress, and Boris Johnson gave in under pressure produced by the revised model.

This is all Britain-centric, but the same thing has been playing out throughout the West. The UK strategy was not an outlier, it was the standard pandemic response used by international organisations and governments, just presented a bit more transparently than in other countries. Most governments have backed away from it, and are in this no-mans-land of lockdowns and no long-term prognosis. Sweden seems to be the only place going ahead with it at this point. To this day, the government is only officially talking about slowing down the spread, but is happy for people to think it is trying to prevent it.

The critical question, from the 12th March, was whether the Asian countries that appeared to be “winning” against the virus could sustain that. As of 28th March, that still isn’t clear. South Korea and Taiwan still seem OK. Japan and Hong Kong are getting a bit of a resurgence of cases. Nowhere is fully back to normal except parts of mainland China away from Hubei province.

Anyway, it was the following week that the masks thing started to really come up with a vengance. From the beginning, we were told not to wear masks, that they didn’t help, and they were in short supply for hospitals so we shouldn’t disrupt supply. Most of my twitter timeline has settled on the theory that masks are the one vital difference between Asia and the West that has enabled the former to get numbers down, where they are still growing throughout the latter. This is pretty plausible, but I note it is a long way from proved.

I need to mention somewhere that there is an amazing split between twitter and the outside world. Both Trump and Boris are at all-time highs in popularity, while twitter is 90% screaming at them — even from their supporters — for being evil and incompetent.

20th of March was when @MorlockP got locked out of his twitter account. From reports, it was not an actual suspension, it was the same thing as happened to me — they demanded confirmation by SMS, but he no longer has the phone number.

I think I’m the only one making the case that half a million extra deaths in the UK would not be all that big a deal. It would be about double the normal rate for the year, mostly elderly. I mentioned that I think I’ve had one elderly relative die, generally of respiratory disease, every year for the last few, and if it were two or three one year that wouldn’t show up as a catastrophe. Yes, younger people die of it too, but rarely. It is unlikely that anyone you know under the age of 60 would die, though quite likely that you would know someone who knew someone who died.

Related, I’ve expressed scepticism about the “health system breakdown” stories. Not that it’s unlikely — it’s likely to happen. I just don’t think it’s happened yet, anywhere. We have detailed stories from one hospital in Lombardy and one in New York. Meanwhile both systems are publishing statistics that show they are not (yet) overloaded. See for instance this March 13 report from Lombardy. That was two weeks ago now, but the first “collapsed” stories I saw were from before that. The reporting I’ve seen saying there is a collapse has been Damien Day style TV, with no detail or authority comparable to that JAMA session.

The other part of this is that people are jumping to conclusions about things they don’t know about based in implications of media reporting, which is a very dangerous thing to do. As I have repeatedly observed, Triage is standard practice in the NHS, and hospitals frequently get overloaded and don’t have beds for everyone. Enormous emphasis has been put on supply of ventilators. From early on, we were told that was the critical factor, that there would not be nearly enough ventilators in intensive care units for every COVID19 patient that needed one.

My experience, that I mentioned above, of relatives dying is that elderly patients with respiratory problems are never put into intensive care. I don’t know if with an infection like this one they generally would be, but nobody has actually said that they would — it’s just been left as an unstated implication of news reports. It’s hard to find the answer, because it’s not something people talk about. Anyway, I don’t know.

However, the reality is, if you just find extra space and beds for patients until they die or get better, then my expectation is that the effect of this pandemic would be otherwise not noticeable to the general population. It would be a very distinct peak in any statistical treatment, but in concrete terms all it would mean that if you knew of twenty old people who died over a ten year period, three or four of them were in 2020. Stalin was exactly right: one million deaths is a statistic. If spread over months and a big country, it’s not a directly observable event.

(One other possibility is that for many, none of them would be in 2021. One reason why this pandemic is more deadly is because we are able to keep people alive for whom every breath is an effort. Were our lives less easy, there would be many fewer in that state).

Also for these reasons, I expect the pandemic to be a non-event in the third world.

This last week (from March 22nd), the conversation has mainly gone to the economic effects (“Money printer go Brrrrr”) and outrage over the still-continuing anti-mask propaganda from Western agencies, as well as the past anti-travel-restriction propaganda from media, governments and NGOs that was continuing well into February. The Lancet condemned travel restrictions on 13 February

There was a bit of a fuss on the 24th over a model published by an Oxford epidemiological group suggesting that possibly over 90% of infections are asymptomatic and that therefore we could be already halfway to herd immunity. This was quite useful as a reminder that we don’t really know how many people will suffer, but there’s no reason whatsoever to assume that it’s that low. The model used only early case data from Italy and the UK to calibrate. Inevitably, media reporting of the publication was absolutely execrable.

On the 25th, in response to completely non-existent popular demand, I published my own pandemic modelling code on GitHub. While the actual model is of little relevance, some of the conclusions I drew from the process may be: “

Of course, nobody would really rely on such crude mathematical treatments when planning for unlikely events, would they?”

So that’s where we stand today. This isn’t a series, it’s a record. I will append to this piece as I go along. As such I don’t think it’s a useful focus for discussion, so comments should go on Twitter or under other posts with more focus.